When 26,000 Chicago Teachers Union members hit the picket lines Monday, Mayor Rahm Emanuel called it a “strike of choice” that is “unnecessary,” “avoidable” and “wrong.” He stayed with the narrative he’s been pushing for more than a year – that teachers are acting selfishly upon their own interests at the expense of students and parents.

Talking with some of the thousands of teachers, school nurses, counselors and other staff who manned picket lines and rallied downtown Monday and Tuesday, I also got the impression the strike was a conscious “choice.”

Not a choice to throw the lives of students and parents into chaos in a bid to get better pay and less scrutiny, as Emanuel’s administration has painted it, but a choice to stand up to a powerful city administration and well-funded national “education reform” interest groups in a battle that epitomizes larger fights over public sector unionism and the future of public education nationwide.

Judging from the throngs of parents, other union members and regular Chicagoans who marched with the teachers, there is strong support for this choice. Throughout the city as teachers in their trademark red T-shirts picketed outside schools, horns blared nearly nonstop in solidarity. The Chicago Sun-Times reported that in a 500-person poll taken Monday, 47 percent of Chicagoans support the teachers strike while 39 percent oppose it.

Tuesday’s negotiations reportedly wrapped up with no end to the strike in sight. Emanuel’s administration said only a few issues remain to be worked out, including “merit-based evaluations” and job options for teachers laid off from schools that are closed for poor performance. But the union indicated many more chokepoints remain.

“It is not accurate to say both sides are extremely close—this is misinformation on behalf of the Board and Mayor Emanuel,” said Chicago Teachers Union spokesperson Stephanie Gadlin in a statement early Tuesday.

At the second consecutive mass rally outside the Board of Education headquarters downtown Tuesday afternoon, thousands of teachers and supporters made clear that Chicagoans see the strike as about more than salaries, job security, and even class sizes and standardized testing. Rahm Emanuel was dubbed “Mayor One Percent” early in his term, and many protest signs and speakers framed the teachers strike as a battle for the rights of working people including teachers and public school parents and students alike, versus the interests of corporations and wealthy power-brokers.

Along with the high-profile struggle with the teachers union, Emanuel has also picked fights with public sector unions AFSCME and SEIU since taking office in May 2011. Among the points of contention: the closing of public mental health clinics and libraries meaning the loss of union jobs; the privatization of airport concessions, janitorial services and other public positions; and the awarding of previously union janitorial contracts to non-union firms with records of labor law violations.

Though unions in Chicago, like elsewhere, are much weaker than in their heyday, the city’s proud labor tradition has been on display during the teachers’ strike and its buildup. Public and private sector workers including nurses, janitors, pilots, firefighters, police officers and factory workers have joined the marches, picket lines and solidarity rallies. The Chicago Teachers Union (CTU) strike headquarters are housed in Teamster City nearby other long-time union headquarters on Ashland Avenue just west of downtown.

On Tuesday, SEIU Local 1 gave the two-day notice required for their members to honor CTU picket lines, meaning as of Friday school janitors can refuse to go to work in solidarity with striking teachers.

“We need to stand in solidarity here,” said SEIU Local One president Tom Balanoff outside the Board of Education Tuesday. “Workers all over the country and this city are being pushed down, and we need to fight back.”

Mae McLeninen, 62, has been “around the public schools since 1969,” in her words, as a parent, grandparent and for the past 16 years as a school janitor and shop steward. From her position she sees first-hand how hard teachers work, she said, and how dwindling resources and growing class sizes have made it even more difficult for them to do their jobs.

“They spend their own money to buy supplies for students, they are great educators, and they have 30 to 40 students in a classroom,” she said at the downtown rally Tuesday, with her tiny great niece and great nephew – future CPS students – in tow. “All over the world people are watching Chicago, hoping the teachers can make it better for people in Wisconsin and Minnesota and other places. I want to say to Mayor Emanuel that in his father’s and forefathers’ time, we had unions so people could retire and have a pension. So now he needs to sit down with teachers and come to some of these ghetto schools and stop bickering so we can really solve the problems.”

Emanuel has consistently espoused his concern for Chicago students and has framed his insistence on a longer school day – the opening sally in his fight with the teachers union – as key to making sure all Chicago students get a quality education. But teachers and many parents aren’t buying it, saying that if Emanuel really cared about students he would listen to teachers and parents and find a way to fund more enrichment programs, resources and smaller class sizes.

Though Emanuel took office facing a $700 million budget hole in the public school system, teachers and other critics say he could find ways to plug it if his priorities were different. They point to millions of taxpayer dollars diverted to huge corporations including United Airlines and Sara Lee Corp. through the Tax Increment Financing (TIF) program, which funnels property tax dollars to public and private projects meant to develop “blighted” areas.

“Silly rich guy, TIFs are for kids,” said signs produced by the teachers union.

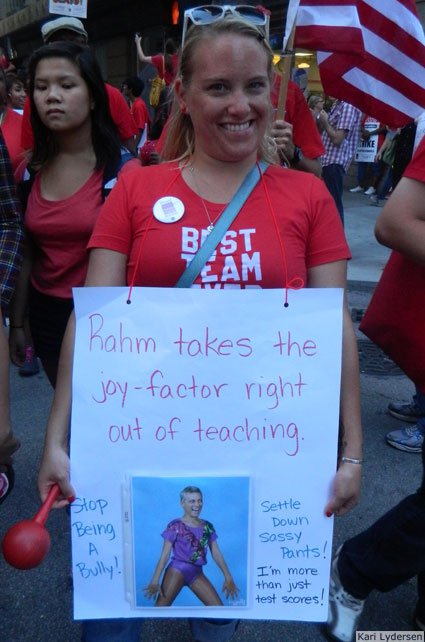

Many homemade signs and chants directly targeted the mayor.

“Hey hey, ho ho, Rahm Emanuel has got to go!” shouted protesters. “Hey Rahmold Reagan, don’t privatize public ed,” said one sign. “Hey Rahm, CPS has a strict no bullying policy,” said another, with many signs riffing on the notion of Emanuel as a bully.

Critics of the teachers’ union have praised Emanuel for taking a hard line against the union whereas they say past administrations – most notably former Mayor Richard M. Daley – caved in to union demands to avoid strikes. They note that union teachers make on average more than $70,000 a year, more than double the average Chicagoan.

Though the union has demanded salary increases especially in light of a longer school day, they have repeatedly stressed that money is not the primary issue. Rather it seems quite clear to all involved that the knock-down drag-out contract negotiations are really about the future of public education, including the role of unions and non-union charter schools and the extent to which teachers are evaluated with corporate-style metrics based on student performance on standardized tests.

Proponents of these tests say such metrics are key to making sure only quality teachers remain and advance in the system. Teachers on the picket line outside a bilingual elementary school in the immigrant neighborhood of Pilsen on Tuesday countered that such metrics will only force teachers to eschew schools in the most troubled communities in a desperate bid to keep their jobs.

At the downtown rally Tuesday, union president Karen Lewis decried “outsiders” who sit in air-conditioned offices and “use spreadsheets” to determine the future of public schools. (The lack of air conditioning in many public school classrooms has been a recurring theme throughout the negotiations.)

“We are a union,” Lewis told the crowd of cheering protesters while taking a break from the negotiating table. “I’m not afraid to say that word. I’m not afraid to say we have more in common with our children and our parents than these rich people who say they know best.”

Kari Lydersen is a Chicago-based journalist, author and journalism instructor. She worked through 2009 as a staff writer for The Washington Post out of the Midwest bureau. She is the author of three books, most recently "Revolt on Goose Island: The Chicago Factory Takeover and What It Says About the Economic Crisis"