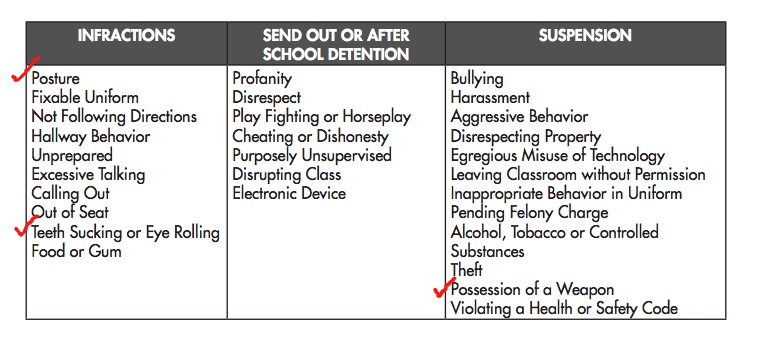

Chalkboard via wikimedia. Figure via pixabay. Following images taken from an online New Orleans charter high school handbook.

Destiny arrived at high school one day with a stun gun.

New Orleans has a crime problem, and because Destiny takes the bus to her job after school, her mother had given it to her for safety on her evening trip home. When the Taser was discovered—she had forgotten to remove it from her book bag—she was threatened with expulsion. Possession of a stun gun is grounds for automatic expulsion, which meant that she wouldn’t be able to return to this school—or any New Orleans school—for a year.

Destiny is a good student, involved in social justice activities, but the expulsion would mean the end of a promised college scholarship.

I went with her as an advocate to the Louisiana Recovery School District’s hearing office, created in 2013 to handle the high number of expulsions happening in New Orleans’ all-charter system.

We won our case and Destiny was allowed to return to school. But watching how the adults responded to her, it was clear to me that they were willing to rescind the harsh judgement because she was an A student. Afterwards, her eyes filled with tears. “What if I had been a C student?" she asked. We both felt sure she would have been expelled.

Destiny said she wanted to help other girls faced with this problem. In a city where crime is a serious issue, lots of girls carry Tasers, pepper spray, and rape whistles—all of which are illegal in the schools. Destiny imagines a “check in and check out” system that will allow girls like her, who work after school or have extracurricular activities that require them to take the bus at night, to legally bring to school the protection they need to get home safely.

I work as a student advocate and trainer in New Orleans schools. My daughter Brandon Bigard and I give regular talks to students around the city about strategies to navigate the school district’s punitive, “no excuses” charter school system. With Destiny’s case in mind, at one recent talk we told the young people we were sorry about the lack of freedom and tolerance in New Orleans schools, and that we thought they deserve better.

Afterward, one young lady described a school where kids aren’t allowed to use the bathroom without permission, where students who struggle with grades are singled out by administrators, and where “no excuses” means that kids dealing with traumatic situations, like a relative getting shot or thrown in jail, aren’t allowed to have a bad day.

“When students start standing up and speaking out, they get detentions and they get suspended,” she said.

When I asked about counseling at her school, she laughed. The “counselor” on site isn’t actually a counselor, she explained, but a single teacher overwhelmed by the sheer number of students who seek her out. And she’s powerless to to overturn administrative decisions, so she can do nothing to remedy the situations that many students experience as unfair.

“You can get demerits for literally anything,” said John, another student. School officials tell students that they are being prepared for the real world, he explained. But, he went on to say, “I think that in most jobs, people can use the bathroom when they need to. They don’t get fired for not sitting the way their boss want, or for having their office a certain way.”

I asked if he thought there was anything that could change his school for the better and his answer was clear: “Treat us like human beings. Stop punishing us for every little thing.”

My experiences working with these students have inspired me to try to find a way to support them: to provide them with an outlet, so they can talk about their experiences, and to connect them with decision-makers so that can they actually change things in their schools. The program I have in mind combines youth advocacy and solutions, in which young people talk not just about what they don’t like about their schools, but about specific ideas for making them better.

Here are the building blocks:

- Anonymous reports: Students can document what’s happening in their schools and identify problems without fear of repercussion;

- Community liaisons: Adults, including church leaders, academics and educators, can assist students with school-related problems, including the urgent need for counseling;

- Youth liaisons: Students are the experts on what’s happening in their schools. By connecting students in schools across the city, they can begin to document problems and articulate solutions;

- Accountability: Student reports on positive and negative developments in their schools would form the basis of a real accountability system.

This is just a beginning. In New Orleans, we need to stop punishing first and asking questions later. We need to empower students to solve problems, rather than placing them in rigid “no-excuse” hierarchies that ignore the larger contexts of their lives.

Ashana Bigard is a lifelong resident of New Orleans, mother of three, social justice organizer, and advocate for children and families in Louisiana. She is Progressive Education Southcentral Regional Fellow.