Erwin Knoll

There are two photos of Erwin on the wall near my desk, one in which he is talking into a microphone and smiling, and one in which he is staring sternly into the camera. These were the two sides of Erwin that those who knew him came to love: An avuncular presence and a fierce advocate.

As I remember, perhaps imperfectly, it was mid-morning on November 2, 1994, when I got the call. Matt Rothschild, then publisher of The Progressive, was the bearer of bad news: Erwin Knoll had died, the night before, at home, in his sleep, of an apparent heart attack. I do recall, precisely, what I said, as I absorbed the shock: “He was a great man.”

Those words still feel true, and still inadequate, on the twenty-fifth anniversary of Erwin Knoll’s death. He was my mentor, the man who jump-started my journalistic career and set the standard to which I aspire. My internship at The Progressive in the summer of 1984 was a life-changing experience, one that helped teach me the skills I needed to land a job a couple of years later at Isthmus, a weekly newspaper in Madison, Wisconsin, a few blocks from The Progressive. (I had a competing offer from the mayor of Milwaukee to join his staff as a speech writer and I asked Erwin what I should do. “I’m from the old school,” he told me, “where the only way for a journalist to look at a politician is down.” I took the newspaper job.)

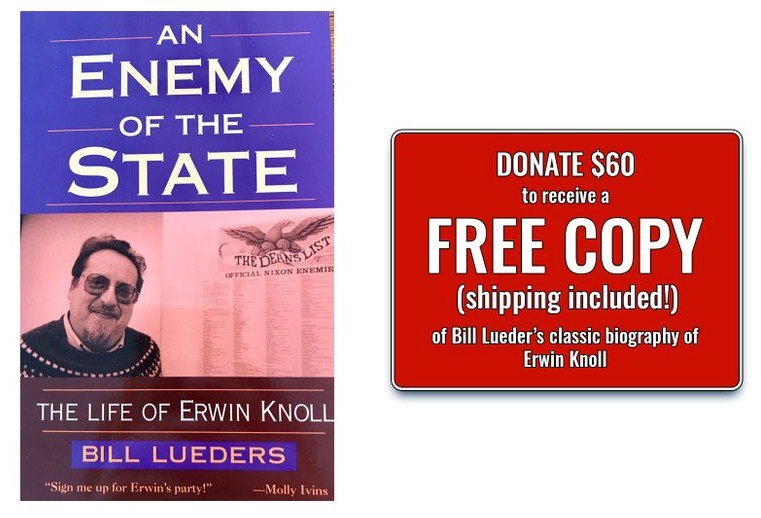

I would go on to write Erwin’s biography, An Enemy of the State: The Life of Erwin Knoll, which came out in 1996, and, after twenty-five years at Isthmus and four at the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism, I found my way to a job at The Progressive, where I now serve as editor, Erwin’s old job.

He could be lacerating; he could be sweet. He held on to his principles—especially his absolute commitment to nonviolence and to freedom of speech—like a barnacle to rock.

There are two photos of Erwin on the wall near my desk, one in which he is talking into a microphone and smiling, and one in which he is staring sternly into the camera. These were the two sides of Erwin that those who knew him came to love: An avuncular presence and a fierce advocate. He could be lacerating; he could be sweet. He held on to his principles—especially his absolute commitment to nonviolence and to freedom of speech—like a barnacle to rock.

As Rothschild noted in his obituary in the pages of The Progressive, Erwin “cared not at all about losing subscribers over political disagreements; indeed, he took a peculiar delight in it, as he understood that it was the price of independence.” (In practice, this sometimes took less elegant forms. “Write me a letter,” I can still hear him barking into the phone, probably to a subscriber. “I don’t have time to listen to your bullshit!”)

Erwin, in a 1985 interview, elaborated: “One of the joys of editing The Progressive,” he said, “is [that] we feel it is part of our job to offend readers. We’re not here to stroke them but to provoke them. It’s a poor issue of The Progressive that doesn’t make a chunk of its readership angry.”

Around this same time, when the head of a national advocacy group responded to the magazine’s decision to accept an ad from a pro-life group by cancelling its subscription and announcing it would no longer help The Progressive financially, as it had in the past, Erwin replied: “We will do our best to get along without your subscription and without your financial support, because as much as we prize both of them, they don’t mean nearly as much to us as our integrity and our commitment to freedom of speech.”

Erwin Knoll, more than anyone I’ve ever met, lived on the edge of history. He had an almost Zelig-like knack for ending up in historical hotspots. He was born in Vienna, Austria, in 1931, and fled the Nazis with his family when he was a young child; about a third of his immediate family members were killed by the Nazis, including a two-year-old cousin. He ended up in New York City, where he considered himself a refugee. He went from not knowing a word of English, to mastering it.

In college at New York University, Erwin, as editor of the student paper, clashed mightily with administrators and a famous conservative professor, Sidney Hook, who poured his energies into purging the campus of suspected communists. He worked as a reporter and editor for an education publication and ultimately for The Washington Post and Newhouse News Service, where he covered President Lyndon Johnson. At The Progressive, he found himself at the center of a historic confrontation between the rights of the press and the power of the federal government over the publication of an article about H-bomb design. And then, he used his perch at The Progressive to become perhaps the best-known radical in America, and one of the nation’s staunchest proponents of nonviolence and free speech. He even defended the free-speech rights of actual Nazis.

Each of these experiences pushed Erwin to become more radical, more disinclined to accept the constraints and limitations on justice and fairness that others insisted were inevitable. He believed that the proper role of progressives is not to hammer out deals, but to stay true to principles. He knew as well as anyone that being uncompromising is not always the best negotiating strategy, but Erwin was not negotiating. He was insisting.

Erwin died at age sixty-three, eleven years after he became editor of The Progressive, having served for several years prior as the magazine’s Washington editor. He was at the height of his renown, a regular guest on PBS’s MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour, where he was perhaps the most prominent progressive commentator on national television, and certainly the most clever.

Erwin knew as well as anyone that being uncompromising is not always the best negotiating strategy, but Erwin was not negotiating. He was insisting.

One of my favorite Erwin lines came when he was asked about gay people serving in the military. “My own preference,” he said, “would be to exclude them, along with everybody else.”

In the early 1980s, Erwin got a story pitch from a writer who wanted to submit an article to The Progressive but wondered whether this would “automatically” result in his inclusion on “the FBI subversive list.” As he did for virtually every letter that came into the office, Erwin took the time to reply:

“I wish I could assure you that writing an article for The Progressive would guarantee you a place on ‘the FBI subversive list,’ ” he wrote. “Unfortunately, I have no reason to believe that such honors are accorded ‘automatically’ to our The Progressive’s writers. To be on the safe side, your article for this magazine ought to be complemented by other, equally ‘subversive’ activities.” After suggesting various acts of protest and civil disobedience, Erwin concluded: “Then you can go ahead and write your piece for The Progressive secure in the knowledge that your government counts you among its enemies. It’s a grand feeling.”

I often find myself wondering what Erwin would have said about the issues of the moment. But there is no point in trying to guess, because whatever he came up with would have been more witty and astringent and smack-dab correct than anything I might imagine. And that makes his absence feel even more acute.

The epigraph of my book is a quote from one of Erwin’s favorite writers, H.L. Mencken, and it perfectly encapsulates Erwin’s life and legacy:

“The most dangerous man to any government is the man who is able to think things out for himself, without regard to the prevailing superstitions and taboos. Almost inevitably he comes to the conclusion that the government he lives under is dishonest, insane, and intolerable, and so, if he is romantic, he tries to change it. And even if he is not romantic personally he is very apt to spread discontent among those who are.”

Erwin Knoll was not a romantic, but he made being a romantic possible for others, like me.