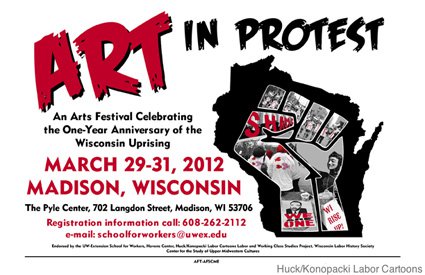

The University of Wisconsin’s School for Workers was planning on hosting an “Art in Protest” festival on campus next month.

Now it’s been canceled.

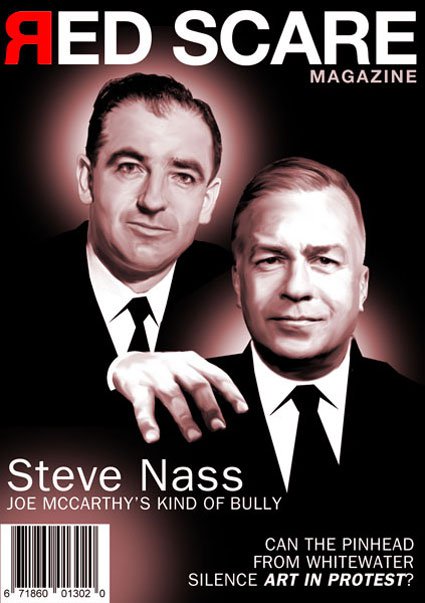

One Republican lawmaker in Wisconsin, Representative Steve Nass, who has been a longtime thorn in the university’s side, was unhappy about the exhibit, and his chief of staff, Mike Mikalsen, gave an earful to the director of the School for Workers last week, suggesting that the exhibit could imperil the school’s funding.

This morning, Corliss Olson, the director of the School for Workers, after consulting with other faculty, sent out an e-mail canceling the program.

“I regret to inform you that the School for Workers has concluded for a variety of reasons that this is not the best time to hold this Labor Arts Exchange,” Olson wrote.

Mike Konopacki, a labor cartoonist who was working on the “Art in Protest” event, is not happy about this outcome, though he sympathizes with Olson’s situation.

“I’m getting e-mails from artists who are saying, ‘What the hell is going on?’ This is a direct attack on freedom of speech, on freedom of expression, on academic freedom, and on labor education,” says Konopacki. “We were celebrating all the art and creativity that people come up with at these protests. It’s beautiful stuff. We’ve had the largest outpouring of protests in the state’s history, and the School for Workers is not allowed to display this?”

Konopacki is worried that the Republicans in the Wisconsin legislature want to kill the School for Workers, which was founded in 1925 as part of the University of Wisconsin Extension.

“The School of Workers survived McCarthyism,” he says. “It may not survive Walker.”

Director Olson also seems worried.

“Our concern,” she tells The Progressive, “is with the long-term ability of the school to serve workers and their organizations from a variety of political stances and viewpoints, as we have done for the last 87 years.”

Olson met with Mike Mikalsen, Rep. Nass’s chief of staff, on Feb. 15.

Nass and Mikalsen had seen a flier for the exhibit, which showed a fist overlayed on the outline of the state of Wisconsin—an iconic image from the labor protests over the last year. And they weren’t happy about it.

“There are people from both sides of the issue who are paying taxes, and the question was whether this was an appropriate activity for the university,” Mikalsen tells The Progressive. “And the timing was a question. We’re just going into a recall election. Was this something the UW Extension wanted to get into at this point in time?”

Mikalsen says he also told Olson that some of the protests against Gov. Walker and the Republicans had gotten out of hand, and if something like that happened at the exhibit, “the consequences of that kind of activity would fall on the extension. They would have to own it.”

Mikalsen denies that he out-and-out threatened to defund the School of Workers, though he says he told Olson that this is a “very tense time,” and that an exhibit likes this “makes it very difficult” to cooperate with the university.

“If something were to occur that would anger the Republican side or conservatives around the state, it would make it hard to continue to work cooperatively,” he says. “Cooperation is a two-way street.”

The exhibit, he said, could be “a festering sore” for the state-funded university.

Mikalsen says he and Nass “tried to be proactive” on this issue. “Rather than waiting till after an event comes off and then criticizing it after the fact, we tried to do this up front.”

Corliss says the School for Workers hopes to celebrate labor art at another time.

Addendum:Here is a statement issued by the School of Workers Tuesday afternoon:

The School for Workers is the oldest university-based labor education program in the country. One of the first operational components of the Wisconsin Idea, the School and its faculty have long brought teaching, research, and outreach to thousands of workers, unions and employers throughout Wisconsin and the nation.

Last fall, the School for Workers joined with a number of other individuals and organizations in planning an event, scheduled for March 2012, entitled “Art in Protest”. The event was modeled, in part, on longstanding events on the east and west coasts. These Labor Arts Exchanges are unique festivals commemorating the cultural and artistic expression of working people.

In 2011, Wisconsin’s working people were confronted in ways unseen in decades. The unprecedented citizen involvement in response to the Governor’s proposal to severely restrict the collective bargaining rights of public employees resulted in a dramatic array of artistic expression. Songwriters, poets, quilters, photographers, cinematographers and others have used their craft to convey their emotions and their messages. The organizers of the Labor Arts Exchange wished to recognize the creativity and artistic expression that resulted from these events and offer an opportunity for artists to share their work.

Art work from Wisconsin’s protests has been sought out and chosen by the Smithsonian Institution because of its representation of this historic time. We are living history. The theme, “Art in Protest”, was chosen many months ago to recognize this momentous juncture.

In the course of developing this event, however, concerns were raised that this Arts Festival would be seen by some as a partisan event. While we disagree, we recognize that some might be unable to separate the art from the politics and we have concluded that despite our best efforts, it would be difficult to maintain the primary focus on art and respect for the culture of working people. While we do not hesitate to explore matters of public policy that affect working people and labor organizations, we have reluctantly decided that the March 2012 timeframe is not the ideal time for this first Labor Arts Exchange. We hope to find a more suitable time in the future to commemorate the artistic and cultural efforts of working people and their organizations, celebrating their art and creativity with a broader focus beyond the immediate political discourse.

If you liked this story by Matthew Rothschild, the editor of The Progressive magazine, check out his story “Santorum’s Backwardness."

Follow Matthew Rothschild @mattrothschild on Twitter